It usually happened in his office, one of the rare ones in those days with a computer. Not so rare was the refrigerator full of beer, which would make his office the room of choice for Keith Hernandez, still in uniform, to watch one of the greatest comebacks in World Series history.

It would happen, too, in hotel bars on the road, the usual endpoint to a day’s work of the New York Mets of the 1980s, who like Middle Age marauders would invade your town, fight your team and drink your beer, whiskey or, if it were all you had left, your mead, and then move on to their next conquest.

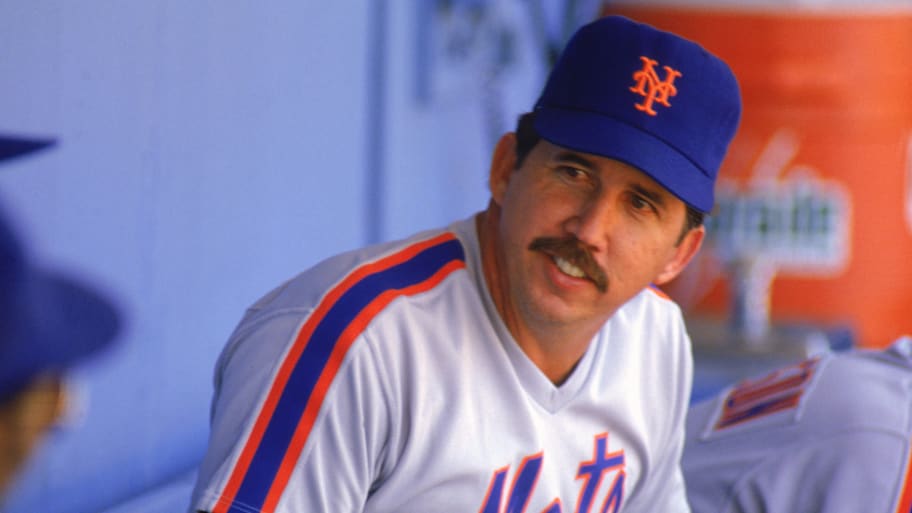

If it happened once, it happened a hundred times. The only elixir Davey Johnson welcomed more than a stiff drink was a second guess. As a young beat writer covering Johnson’s Mets, I learned not to fear questioning the manager but to relish the adventure. Johnson loved it even more. Davey would look at me and Bob Klapisch, another young beat reporter, and in that Southwestern gunslinger style of his—speaking softly and slowly from behind a crooked grin and that droopy mustache, metaphorical tumbleweeds bouncing by—would practically spit out in his Texas drawl, “The problem with you guys …” and here Davey would stop, as he often did in his unhurried cadence, “… is you know just enough baseball to be dangerous.”

“The Last of a Kind” is an overused trope. Life and baseball do not exist in a loop. To be human is to be unique, especially in these days of embracing AI. When Davey died Friday at age 82 after a long illness, I did not mourn his passing against the context of cookie-cutter, execu-speak managers today. I remembered him for his vast reservoir of leadership skills that are timeless.

Johnson, as he often proved to those of us questioning his moves, wore some of the thickest skin I’ve ever come across in a ballpark. His greatest trait was his self-confidence. It was massive, though never arrogant.

He was a decisive decision-maker who loved the responsibility of being the one to make the call. When the Mets fired him in 1990, a mistake when general manager Frank Cashen thought the team lacked “fire in the belly,” Johnson took it well. He told me that if a team were dumb enough to fire him, he probably should not be working for that team.

Davey Johnson lived one of the biggest, craziest and most impactful baseball lives of his generation, at least among those not in the Hall of Fame. He hit 136 home runs as a player and won 1,372 games as a manager, a combination reached only by Joe Torre and Dusty Baker.

He has the eighth highest winning percentage (.562) of all managers with at least 2,000 games. A baseball Zelig, he had the last hit off Sandy Koufax, batted behind Henry Aaron and Sadaharu Oh, was the last manager of Rusty Staub (born 1944) and the first of Bryce Harper (born 1992), was the first manager to lead the Washington Nationals into the playoffs and is the last Reds manager to win a playoff series, the last Orioles manager to win an ALCS game, and, most famously, the last Mets manager to win a World Series.

What the numbers do not define is his fearlessness. When it came time for decisions, public consumption never entered his mind—or the preferences of his own front office.

The 1986 Mets, for instance, lost the first two games of the World Series at home.

“This club was the most down after Game 2 that I’ve ever seen it,” Hernandez said back then. After an off day, Game 3 was scheduled for Fenway Park in Boston. This was the days before interleague play. The Mets had played a meaningless exhibition game there, but few of their players were familiar with the quirky ballpark. Rather than a customary workout on the off day to get acquainted with the park, Johnson gave his players the day off.

“It gave us respite,” said Hernandez, who knew the day would have been filled with more negative questions than fungoes hit off the Green Monster. “To be successful, you’ve got to eliminate the negatives. When you’re struggling you’ve got to eliminate the negative ways.”

Lenny Dykstra hit the third pitch of the game for a home run, Mookie Wilson played the Monster like a Stradivarius and the Mets rolled, 7–1.

In the Game 6 classic, facing elimination, Johnson double-switched his best slugger, Darryl Strawberry, out of a tied game. The Mets rallied to win in the 10th with Strawberry in the clubhouse (Kevin Mitchell pinch-hit a single in his spot) and Hernandez watching on TV in Johnson’s well-stocked office. In the happy clubhouse after the thrilling win to stave off elimination, Strawberry ripped Johnson.

“It made me look bad,” Strawberry said. “Obviously, he didn’t have enough faith to keep me in the lineup. I played and contributed all year and I don’t particularly like that happening in the World Series. Taking me out was a terrible mistake.”

The gunslinger, second-guessed by one of his own, was characteristically unbowed.

“When he said I was taking the bat out of his hands he was thinking of his own personal situation,” Johnson said. “I was thinking two or three innings down the road.”

It was a fine enough explanation, but Johnson could not stop there.

“When Darryl gets a few more years in,” he said, “maybe he’ll be managerial material.”

It was Johnson who dared play defensively challenged Mitchell or Howard Johnson at shortstop—if a flyball pitcher such as Sid Fernandez was on the mound. It was Johnson who first moved Cal Ripken off shortstop to third base—to accommodate Manny Alexander. It was Johnson who shuttled lefty Jesse Orosco and righty Roger McDowell between the outfield and the mound in the same inning. It was Johnson who told Cashen to put 19-year-old Dwight Gooden on the 1984 Opening Day roster. It was Johnson who predicted in spring training of 1986 that the Mets would not just win the division but would “dominate.” It was Johnson who after his Mets trashed the charter plane home from their 1986 NLCS win in Houston, tore up the bill for repairs and told his players, “F--- ‘em. We’re going to win the World Series and make them a lot more money.”

Johnson didn’t care what his players were up to in their off hours. Johnson himself wasn’t in his room reading a novel. He cared only they showed on time (sometimes even that was too much to ask for some of them) and played hard, even if it meant fighting the other team (of which his players were all too happy to oblige).

Much can be said about Johnson’s Mets teams, but two truths are most apparent. One, Johnson was a master at developing young pitching. He was the first major league manager for Gooden, Fernandez, McDowell, Ron Darling, Rick Aguilera and Randy Myers, all of whom broke in between ages 19–24 in a two-year window—and all of whom pitched for 12–16 years in the majors. (The irony here is that Johnson was the Nationals manager during the Stephen Strasburg Shutdown of 2012, when the front office sat a healthy Strasburg to limit his innings as the team lost the NLDS.)

Two, Johnson’s Mets, playing with their manager’s swagger, were one of the greatest rally teams ever assembled. In Game 6 of the 1986 Series they made Roger Clemens in seven innings throw 134 pitches—44 of them were foul balls. They would not go away. They oozed Johnson’s confidence.

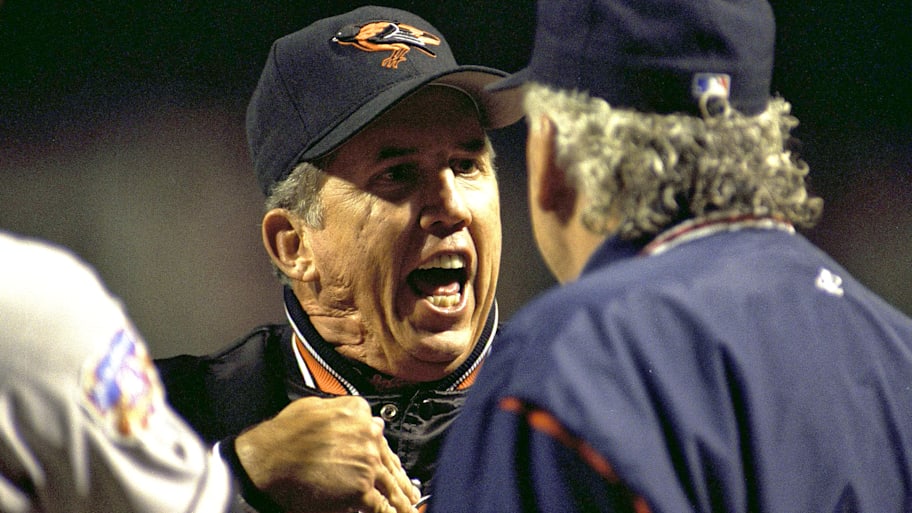

If Johnson had a fault, it was that he did not manage up well enough. He was headstrong, which was a particular problem when your bosses were Cashen and owners Marge Schott of the Reds and Peter Angelos of the Orioles.

After Cashen fired him in 1990, I flew to meet Johnson at his home in Winter Park, Fla. Cashen gave Johnson an invitation to take another job with the Mets. Johnson wanted no part of it. He wanted the power to make decisions, not just contribute to them.

“I’m a field boss,” he told me. “And as a field boss I don’t think my brain was picked enough.”

Cashen hired Bud Harrelson to replace him. The Mets immediately instituted new rules. No golf. No card playing. And … the horror of horrors, a curfew! They won’t work, Johnson said.

“Nope … These are the things Frank wanted,” he said, “but I didn’t think they were needed.”

The oeuvre of Johnson appreciates over time. He was a home run-hitting, Gold Glove second baseman with a degree in mathematics who was one of the first managers to embrace computers and information. Yet it was how he dealt with people that set him apart. He took four different franchises to the playoffs by understanding his players as much as he did how to run a game. He fostered environments for players to succeed and gained so much of their trust he could speak bluntly. Though we have come to assign smarts to the analytical side of the brain, there is genius in that touch, too. Johnson had it.

I did not know it then, but the morning of Oct. 28, 1986, was as good as his managerial life would ever get. Johnson was only 43 years old. The clubhouse carpet was still wet from the one hundred bottles of champagne that were sprayed and spilled after Orosco obtained the final out of the World Series about 12 hours earlier. Johnson was in his office, lying on his back on his couch. He was wearing dark sunglasses. He had barely slept. The Mets were preparing for a parade down the Canyon of Heroes.

The equipment manager, Charlie Samuels, interrupted Johnson’s repose with a bulletin typical of that team.

“Davey, Wally’s not going,” Samuels said, referring to second baseman Wally Backman. “His wife says he’s too sick and he won’t go to the parade. Do you want to call him and tell him he should go?”

Johnson did not move from his spot. “Nope,” he said. “I’m through managing.”

I asked Johnson how he felt. “Aside from the fact that I got only one hour of sleep, I feel good, if you know what I mean.”

I knew exactly what he meant. Davey Johnson had been proved right, just as he knew it would be all along.

More MLB on Sports Illustrated

This article was originally published on www.si.com as Davey Johnson Was a Natural-Born Leader—and He Knew It.