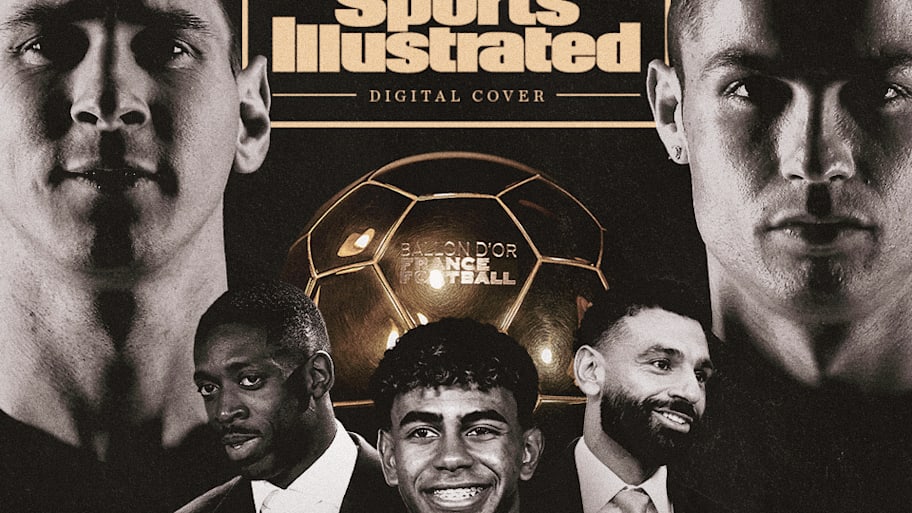

“I told my friends, I don’t dream about winning a Ballon d’Or, I dream about winning many,” Lamine Yamal unashamedly declared ahead of this year’s ceremony.

Barcelona’s ambitious 18-year-old prodigy will be part of the glittering crowd which assembles at the Théâtre du Châtelet this month to discover the latest Ballon d’Or winner, the prize annually handed out by France Football to the standout footballer over the past year. Alongside Yamal’s rival contenders there will be 2,000 of the best and brightest from around the game squashed into the Parisian opera house in their finest black-tie attire. Millions more will watch the drama unfold on various streaming platforms as the results are endlessly dissected and debated over the subsequent weeks, months and years.

When the Hungarian forward Flórián Albert was presented with the 1967 Ballon d’Or, his wife, Irén, was the only spectator at an impromptu ceremony in their kitchen.

Soccer’s relationship with this shining golden orb has morphed from unassuming indifference into suffocating, and at times destructive, obsession. Undoubtedly the most prestigious individual honor soccer has to offer, being crowned the best player on the planet takes precedence over collective achievements for an ever-expanding glut of modern players.

England international Trent Alexander-Arnold is comfortable admitting as much. At the end of a painfully stilted interview last year, the former Liverpool fullback was given the hypothetical choice of ending England’s six-decade wait for a World Cup triumph or lifting the Ballon d’Or. “Don’t play the game; change the game,” was the mantra he provided to justify his blatant preference for individualism.

The startling evolution of the Ballon d’Or is a consequence of many factors. The fall of communism, the rise of social media, Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo have all played their role in a process which has shown few signs of slowing down.

A One Night Stand

“I don’t want to compare the Ballon d’Or to other individual awards,” Vincent Garcia, France Football’s editor-in-chief in charge of organizing the prestigious event, says. “It is unique.”

That it would hold such a lofty standing in the world’s most popular sport was not immediately apparent. Jacques Ferran, one of Garcia’s legendary predecessors who helped invent the Ballon d’Or in 1956, was asked almost 60 years later whether he ever envisaged the impact his brainchild would have on the game he loved. “Absolutely not,” he freely admitted. “The Ballon d’Or, at first, was just another trophy.”

Set out with the harmless intention of crowning the best European player of the year—it would be four decades before players from outside the continent were included as candidates—this was just one concept among many which sprouted during the fertile brainstorming sessions held inside the offices of the French publication. The first season of the European Cup—the forerunner to the modern UEFA Champions League—had been formed just one year earlier by Ferran’s colleague Gabriel Hanot.

A drive to increase magazine sales proved to be the less-than-romantic inspiration for the Ballon d’Or. Instead of following the European league format of an August to May schedule, the award was originally and deliberately handed out at the end of each calendar year to guarantee content for the publication. This, after all, was a time when scores of matches were frequently wiped out by frozen pitches. Pages needed to be filled.

The period of consideration for those voting on the winners was only shifted to match a traditional domestic league season in 2022.

The identity of the judges who cast a vote has dramatically evolved over the years. There were just 16 exclusively European journalists consulted when the English winger Stanley Matthews was heralded as the inaugural victor in 1956, receiving a compact version of the trophy in Blackpool’s clubhouse. Aside from a strained association with FIFA between 2010 and 2015, which balanced votes from journalists with the opinions of international captains and managers, the award has chiefly been the domain of non-playing observers. One journalist from each of the 100 highest-ranked FIFA nations will decide this year’s winner.

With a typically Gallic sense of flair, former France Football editor-in-chief Pascal Ferré once described the original inspiration for the Ballon d’Or as a concept “born with the carefree spirit of a one-night stand.” That dalliance would soon grow into something much more serious.

Butterflies in the Stomach

Given the publication’s association with the European Cup, any honor dolled out by France Football carried some sway. But the glamor it would later promise was still to come. “They gave me the trophy at a normal league game,” Luis Suárez, the spellbinding Spanish midfielder who excelled for Barcelona and Inter, recalled of his triumph in 1960. “Then I went home with the junk as though nothing had happened. There was no big dinner after I received it.”

Manchester United and England icon Bobby Charlton only discovered he had won the 1966 prize after listening to a news bulletin on the radio while his club returned from a Boxing Day fixture against Sheffield United. Charlton had been muzzled in a 2–1 defeat and wasn’t impressed. “I had been voted the best European player. I really didn’t feel like that player,” he seethed years later. “It was a day of disappointment.”

That sense of English disinterest in the award would persist—Michael Owen takes great pleasure in revealing his ignorance about the Ballon d’Or’s existence when he won the trophy in 2001, even if he did list several former winners during his acceptance speech at the time—but its sense of importance would soon spread across the continent.

The first three decades of the award feel like its sweet spot. This is a time when the Ballon d’Or was the consequence of success rather than an aspiration in isolation.

Amid the hundreds of paper clippings Gianni Rivera’s father saved during the wispy Italian playmaker’s stellar career, he holds the four-page spread in Corriere della Sera of the 1969 Ballon d’Or ceremony close to his heart. “I knew I was among the favorites,” Rivera noted, “but I wasn’t under any particular illusions. If I won individual awards, I was happy; if not, I waited until the following year.”

Allan Simonsen’s list of childhood ambitions included becoming a professional player, taking his mother to a match in Italy and representing Denmark at the international level. “But I had never talked about the Ballon d’Or,” he insisted. That’s not to say that the unwitting midfielder was dismissive of the prize when he learned of his triumph in 1977 while queuing up for a grilled sausage. Quite the opposite. “Every day, people talk to me about it,” he would later gush, having swapped the barbecue for some bubbly. “Even today. You have no idea how proud I am to have won this trophy.”

The modern design of the trophy in question is a “very important” factor when considering the growth of the award’s significance, former France Football editor Garcia says “Originally smaller, the trophy was redesigned in 1983, on the occasion of Michel Platini’s first win, to become this gold-covered Ballon the actual size of a real ball,” Garcia explains. “A major innovation, because this trophy is both magnificent and captivating.”

Igor Belanov takes such great pride in showing off the spectacular design he’s had to replace its case twice. The sharpened point at the tip of Valeriy Lobanovskyi’s second great Dynamo Kyiv side claimed the prize in 1986, beating out England’s Gary Lineker—who remains enjoyably bitter about this snub—at a time when only Europeans could be crowned champions, thereby ruling out the unrivaled Argentine, Diego Maradona.

“I had a feeling, I’d felt for a month that I was going to win it,” Belanov reflected. “I was at home, and my mother immediately grabbed a bottle of champagne.” The 100,000 fans in attendance for Dynamo Kyiv’s European Cup quarterfinal against Beşiktaş bellowed in unison as Belanov paraded the gleaming trophy around the Republican Stadium. The joy of claiming the Ballon d’Or lasted long after the sound of cheering had died down.

“I try to show it as much as possible, especially to children,” he said. The Odesa-born, former Soviet Union international even took his Ballon d’Or trophy on a tour of the Ukrainian armed forces in the midst of the war with Russia, regaling soldiers with tales of his triumphs to let them “switch off their brains for a few minutes and escape the horror of war.” That is the power the Ballon d’Or can have.

Shifting Power Dynamic

Hristo Stoichkov was a child of communism. Born in 1966 in Plovdiv, Bulgaria, the fierce striker with a short temper and long list of skills would make his senior debut for CSKA Sofia, the army team. Stoichkov rapidly outgrew the standards of his domestic top flight yet he was barred from moving abroad due to the restrictions of his nation’s political regime. It took the fall of communism in 1990 to open the borders across Eastern Europe.

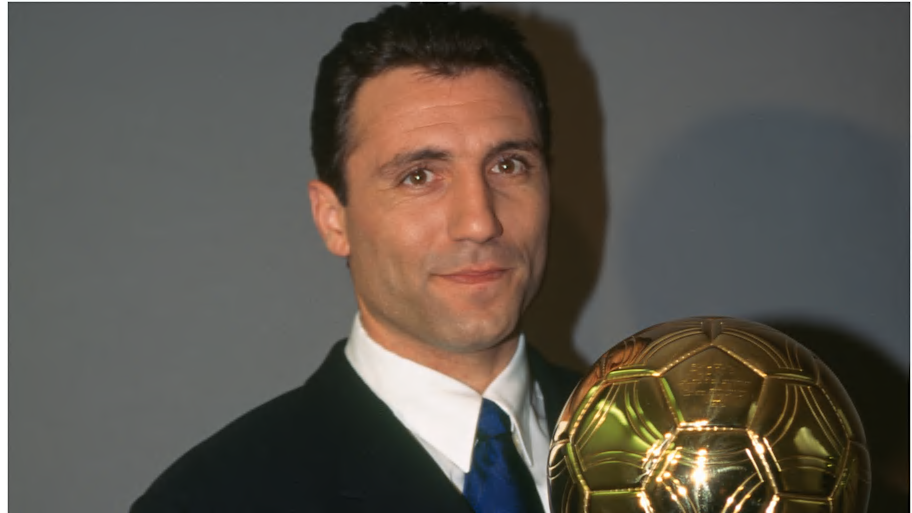

Barcelona promptly pounced. Together with the promise of a red sports car, Stoichkov was convinced by a conversation he had with the Catalan side’s manager, Johan Cruyff. A three-time winner of the Ballon d’Or during the first wave of individualism back in the 1970s, the Dutch coach took Stoichkov under his wing and told him: “I’m starting from scratch with you, we’re going to win that Ballon d’Or together.”

This is one of the first major examples of the Ballon d’Or as a prize to strive for in and of itself. Stoichkov’s stance was only a reflection of his surroundings. The power of the individual filled the void left by communism, as people reveled in their freedom from a system which had so strictly enforced the exact opposite ideal.

The Bulgarian forward would become one of the standard-bearers of Cruyff’s legendary Barcelona side which won four Spanish top-flight titles from 1991–94 as well as the club’s first European Cup in 1992.

That same year, FIFA introduced the back-pass law, prohibiting teams from wasting time by endlessly knocking the ball into the hands of the goalkeeper. This created a more free-flowing spectacle which was only enhanced further by the outlawing of tackles from behind soon after. Never before in the sport’s history had individualistic players—the dribblers, the risk-takers, the archetypal modern Ballon d’Or candidates—been given more favorable conditions in which to thrive.

Much to his chagrin, Stoichkov lost out to Marco van Basten in 1992 before eventually getting his hands on the Ballon d’Or two years later. At the sight of his name etched into a plaque on the jagged rock-face stand, Barcelona’s strongman broke down in tears. “Now I’m never letting go,” he wailed.

When George Weah won the following year’s award, he whispered to himself: “I think I’m going to die.” The shock had worn off three days later only to be replaced with a sense of unbridled glee. “It’s heavy,” Weah beamed after being handed the trophy, caressing the throbbing orb while one of his friends filmed the process on a camcorder. “I’ll distribute the cassettes,” he promised ahead of a triumphant press conference back in his native Liberia on Boxing Day.

Weah’s triumph is a staging post in the award’s history as he became the first—and so far only—African recipient. France Football extended their pool of candidates to players of all nationalities in 1995, reflecting the globalization of the sport and the world at large. “One could almost regret that these innovations did not come earlier,” Garcia admits. It’s instructive that Weah’s mindset shifted once he became a viable candidate. “I told myself that I was going to do everything, not necessarily to be elected but to be considered,” he explained.

“This Ballon d’Or is for the whole world,” Weah gleamed, that initial morbid reaction quickly forgotten. “I’m doubly proud.”

Such was the award’s growing appeal, it inspired a character as introverted as Zinedine Zidane to toot his own horn. “I’ve never been the type to say, ‘I deserve this or that.’ But with that Ballon d’Or in 1998, I was showing off a bit,” the elegant Frenchman admitted. “It wasn’t really me, but I really wanted to win it.”

Not only was it a prize players now openly craved, but clubs wanted to boast a winner of their own. Zidane’s Real Madrid teammate Luis Figo was handed the Ballon d’Or in 2000. Much of the wondrous wing play he performed to win the trophy was carried out during his time at Barcelona, which had only ended in controversial circumstances a few months earlier. On his first trip back to Camp Nou, the Catalans’ physio Ángel Mur asked for a photo of the Portuguese forward with his Ballon d’Or to go alongside the club’s other winners. When Figo returned to his former home the next year, he saw that the framed picture had been doctored; his shining white Real Madrid jersey was colored red and blue. Figo’s Ballon d’Or triumph had been quite literally reclaimed by Barcelona.

Obsession Takes Over

The Ballon d’Or may have been open to every player scattered across the world, but for an unprecedented decade, it was exclusively reserved for just two individuals. Between 2008 and 2017, Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo shared the prize five times each.

Messi and Ronaldo’s rivalry is a uniquely modern phenomenon. There have been clashes between individual players in years gone by, but the longevity and intensity of this head-to-head—in the eyes of the public at least—was a consequence of circumstance. Two years before their Ballon d’Or tyranny began, Twitter was launched. The digital town square soon became the perfect medium for endless slanging matches between one-eyed fans of either player. And that’s the point; an increasing number of new soccer enthusiasts were not so much in favor of Barcelona or Real Madrid as they were fans specifically of Messi or Ronaldo.

In the perennial argument to establish the greatest of all time, the Ballon d’Or became the ultimate scoreboard.

This supposedly extended beyond social media. “Ronaldo has only one ambition, and that is to retire with more Ballons d’Or than Messi,” former France Football editor Ferré claimed in 2021, “and I know that because he has told me.” Ronaldo denied ever uttering those words but Messi admitted that the pair “fed off each other” during what he hailed as a “golden era.”

The light didn’t shine on everyone. While Messi and Ronaldo will rightly go down as two of the greatest to ever lace up, there were occasions when mere mortals put together 12-month bursts to rival even that illustrious pairing. Yet, such was the blinding glamor of the Messi-Ronaldo duopoly, no one else could get a look in. Wesley Sneijder was the attacking centerpiece of José Mourinho’s treble-winning Inter Milan side in 2010, yet he finished fourth in the Ballon d’Or voting. Franck Ribéry lifted five major titles in 2013 for Bayern Munich and still failed to climb above third—much to his fury.

“It was the perfect year,” Ribéry would fume years later. “I couldn’t have done better. This Ballon d’Or will forever remain an injustice. I’m still looking for an explanation.”

The explanation for the voters’ decision is much less interesting than the rage it caused in Ribéry. Ronaldo’s staggering goal record—he scored 44 times in 40 appearances that year—would be enough to sway any less-than-rigorous judge, particularly at a time when international captains and managers voted together with journalists. Yet, to be so incensed by this perceived snub more than a decade later underscores the weight it carried. It works both ways. To many casual observers, Ribéry is almost entirely defined by his failure to win the Ballon d’Or.

In the years that followed, it would become apparent that this feverish obsession with individual glory was increasingly commonplace.

“I think the modern world is too much about individuals,” Arsenal’s historic manager Arsène Wenger said shortly before the ceremony in 2015. “I’m against the Ballon d’Or, I’m against all these things. I’ve seen careers destroyed because the players are too much obsessed to get individual rewards.

“… I feel sometimes it encourages selfishness and people inside the game to go too much for their own sake when some players are in a better position. Even the agents sometimes motivate the players to get individual rewards because they are more valuable on the market after.”

Mourinho, Wenger’s fiercest managerial rival, agreed. “In this moment, football is losing a little bit the concept of the team to focus more on the individual,” he sighed. As did Pep Guardiola.

“When I hear so many times, I always dream of winning the Golden Ball, the Ballon d’Or, these kind of things, that is ridiculous,” Guardiola said in 2017. “It makes no sense. Win the titles, make the people happy. But it is not the way it was before.”

Modern Reality

Luka Modrić was the first to break up the Ronaldo-Messi reign in 2018. When the crafty Croatian playmaker discovered that he would be the one holding the hulking trophy after winning the Champions League and leading his nation to the World Cup final, he “cried like a child,” according to Ferré.

“It is Christmas for them,” the former editor of France Football explained. “It is the only chance you get in a team sport to celebrate by yourself.”

The Christmas analogy is fitting. Soccer players seem to be transported back to childhood when it comes to the Ballon d’Or. “We were all children once,” Real Madrid forward Kylian Mbappé said. “And we’ve remained so, a little. Faced with this glittering trophy, we all become kids again.”

Mbappé and the current generation of potential Ballon d’Or winners were kids when they saw the importance of the award swell during Messi and Ronaldo’s domination. Just as a formative World Cup can spark a love affair with the sport, this idea of the trophy’s significance was etched onto the brain of 10-year-olds all over the world who now see no reason why they should hide their rampant ambitions.

“We all watched that ceremony with those red carpet arrivals and said to ourselves: One day, that will be me.” Mbappé said. “The Ballon d’Or reawakens our childhood dreams. We’ve won titles, other awards, but this one is the holy grail. It’s the ticket to the big world.”

As a Parisian kid obsessed with soccer and raised on copies of France Football, Mbappé is a prime candidate for Ballon d’Or indoctrination. But this is not a localized phenomenon. Players from all over the world are increasingly forthright in their ambitions. As Alexander-Arnold unashamedly admitted, it has even managed to pierce English isolationism.

At times, it can feel as though the pursuit of the Ballon d’Or supersedes the action actually unfolding on the pitch.

As Jude Bellingham collected a stray pass from Ian Maatsen and rolled it nonchalantly into the stride of Vinícius Júnior during the 2024 Champions League final, Rio Ferdinand raised the microphone to his lips. In his capacity as the secondary co-commentator for TNT Sports, the former England international did not offer any critical analysis of Borussia Dortmund’s flawed buildup or the optimistic starting position of Real Madrid’s forwards. Maatsen’s heartbreak and Vinícius’s clinical edge were overlooked in favor of a very telling stream of consciousness: “Ballon d’Or, Ballon d’Or, Ballon d’Or, Ballon d’Or, Ballon d’Or, Ballon d’Or, Vinícius has just taken the Ballon d’Or.”

Many may rail against the notion that Ferdinand stands as a sound representative of the soccer world at large—fair enough—but in this instance, he is not alone. When Vinícius scored a hat trick against the same German opposition in a Champions League match four months later, six days before the 2024 award ceremony in Paris, the crowd at Madrid’s Santiago Bernabéu chanted, “Ballon d’Or, Vinícius Ballon d’Or” with even more frequency than Ferdinand.

Ironically enough, Vinícius didn’t even win the trophy. Manchester City’s defensive midfielder Rodri claimed the glory in one of the narrowest victories in the award’s history. Once rumors spread on the day of the ceremony that the Brazilian would not be recognized for what had been a triumphant individual campaign, Real Madrid as an institution reportedly instructed a club-wide snub of the ceremony. Garcia grimly describes this as “the most spectacular protest” in the award’s history.

“It’s a bad memory for me,” he says, “and it was very complicated for the organizers to deal with this at the last minute, especially since Real had won many other awards.”

The club’s absence meant that manager Carlo Ancelotti was not there to collect his trophy for the best men’s coach of the year and created a particularly awkward moment when no representative of Real Madrid was present to receive the award for best men’s club side of 2024. Reports suggest that another boycott could be enforced in 2025. It all feels a long way from Flórián Albert’s kitchen.

Despite Real Madrid’s protests, the feverish reception of the award continues to rage on. Paris Saint-Germain’s Ousmane Dembélé is the favorite for this year’s main prize and has routinely found himself greeted at matches with shouts of “Ballon d’Or, Ballon d’Or.”

The supremely two-footed forward enjoyed a stellar campaign as the roving fulcrum of PSG’s all-conquering attack. Flanked by fellow Ballon d’Or nominees Désiré Doué and Khvicha Kvaratskhelia, Dembélé was the leading scorer for the PSG side that romped to the club’s first Champions League crown while also lifting the French top-flight title and major domestic cup.

Hoisting aloft the big-eared trophy is seen as a prerequisite for Ballon d’Or consideration. Unlike many modern fascinations, the correlation between international glory for your club and individual recognition has existed almost since the award’s inception. Three of the first four Ballon d’Or winners were reigning European champions. This association has only been heightened in recent years. Mohamed Salah toppled scores of records while leading Liverpool to a dominant Premier League title in 2024–25 but has little chance of winning the award after getting dumped out of the Champions League as early as the last 16—against PSG, thanks in no small part to a goal from Dembélé.

“The Ballon d’Or winner should be in a team that has won the Champions League,” Ronaldo bluntly admitted, even if he and Messi have been able to buck that trend on occasion.

PSG’s domination of the 2025 nominees list is intrinsically linked to their rampant European run. Nine of the starting XI which delivered a nut-and-bolt dismantling of Inter in the Champions League final found themselves on the 30-player shortlist.

Yamal’s failure—if that’s not too strong a word—to lead Barcelona to that showpiece fixture will no doubt count against him and his teammates when this year’s votes are tallied. As much as he has lamented his lack of a Champions League crown, the desire to be individually recognized burns just as fiercely, if not more. At 18, he is part of the generation that cannot remember a time before the modern obsession with the Ballon d’Or.

“It’s a trophy everyone wants to win,” Yamal shrugged, “whoever says they don’t is lying.” Not many bother maintaining the pretense these days.

This article was originally published on www.si.com as When Did the Ballon d’Or Get So Big?.