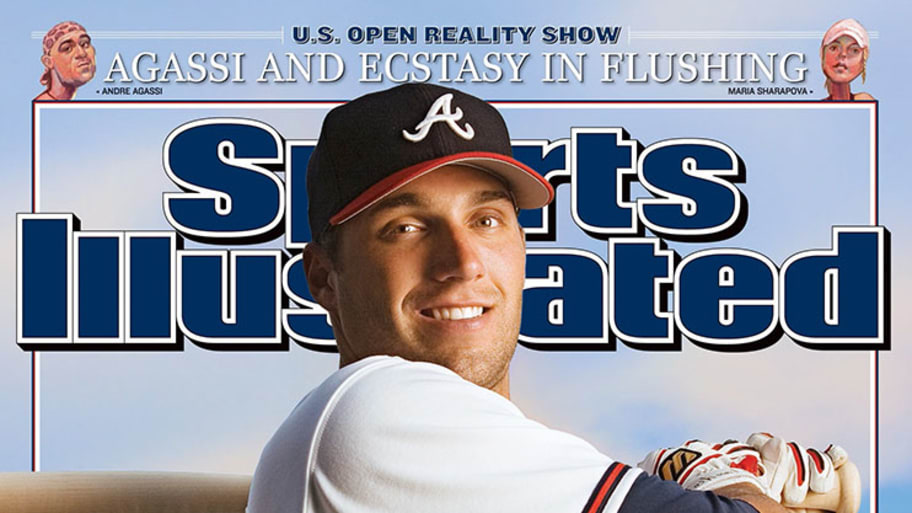

The first time Jeff Francoeur saw his Sports Illustrated cover was on the afternoon of Aug. 22, 2005, when Atlanta media-relations head Brad Hainje slapped three dozen copies of the magazine on the table where Francoeur was playing cards with Chipper Jones.

The next time Francoeur saw it was a couple hours later, when he went 0-for-3 with three strikeouts against the Chicago Cubs and returned to the clubhouse to find his teammates had hung the cover in the shower. “THE NATURAL,” the cover read. “Atlanta Rookie Jeff Francoeur Is off to an Impossibly Hot Start. Can Anyone Be This Good?”

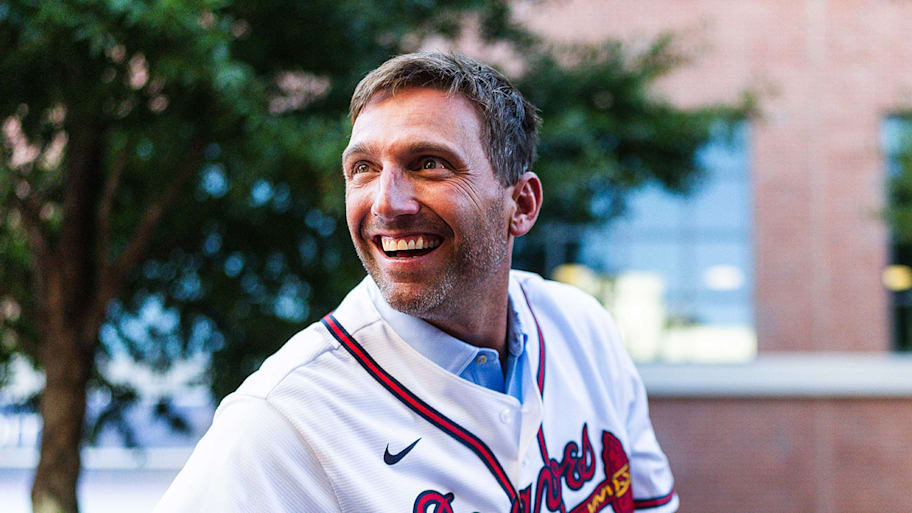

“They just wore me out,” he says, still beaming two decades later. “It was one of the greatest honors of my life, especially being 21 years old. … It was kind of like, ‘Man, I’ve made it.’”

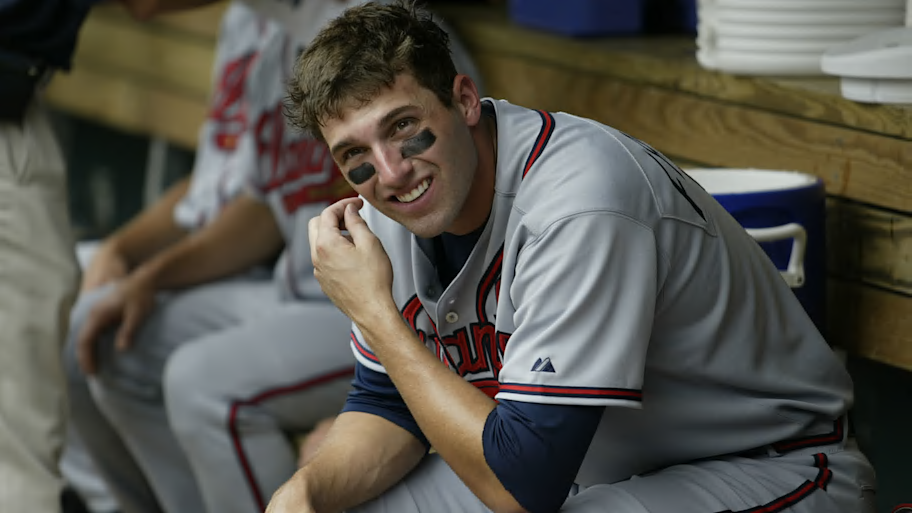

He was three years out of Parkview High School in Lilburn, Ga., he didn’t know how to tie a tie and he was setting the major leagues on fire. He hit .370 with 10 home runs in his first 34 games for his hometown team. Every night at Turner Field he’d hear his childhood friends and high-school football opponents ragging him. He couldn’t imagine how life could get better.

He’d grown up on SI, devouring the magazine every week. (“Except the Swimsuit Issue,” he says. “My mom would take that away from me, but my brother would always sneak it back to me at some point.”) So when writer Michael Farber showed up to write a story about him, complete with cover possibility, Francoeur was giddy. He was also wary of his teammates’ reaction, so he requested that they do the photo shoot first thing in the morning, before any of the other players arrived.

But once the story made the cover, there was no hiding from the hype. In the story, Farber explains to Francoeur that in Bernard Malamud’s novel The Natural, unlike in the movie version, Roy Hobbs strikes out. “That’s why books suck!” Francoeur bellows.

“No, the reason books—or at least baseball novels—often disappoint is that authors conjure preposterous characters and absurd situations to heighten the drama,” Farber writes. “Say some hack writer invents a handsome, strapping young baseball player (aren’t they all handsome?), nicknames him Frenchy (trite), puts number 7 on his back (a la the Mick, lucky number, cheap symbolism) and summons him from the minors to bolster his talented but sagging hometown team (so 1920s). The kid proceeds to hit about 100 points higher in the majors than he had in Double A (a fanciful conceit), smacking homers and gunning down runners, all the while singing along to the soundtrack in his head (you’ve gotta be kidding!) and lifting the local nine into first place. Not even Hollywood would buy it.

“Yet since July 7, when Francoeur was called up from Double A Mississippi and became the 10th rookie on the Braves’ roster at the time, that bit of fiction has become fact—right down to the singing.”

Indeed, Francoeur slept in his childhood bed the night before he debuted. His mother, Karen, made him pancakes. Eventually the veterans started fining him and catcher Brian McCann, another local kid, $20 for every night they lived at home; they realized they were going to pay more in fines than they would have in rent on an apartment, and they moved in together.

Francoeur was living his dream. Until the league started adjusting to him, and he couldn’t always adjust back. After that first, impossible season, he hit .266. Fans labeled him a disappointment. He had breezed through high school and the minors, and he found himself completely unequipped to manage failure in the majors. And doing it in front of everyone he’d ever known exhausted him. Those high school acquaintances’ jokes began to feel more like taunts. His parents would go out to breakfast and answer questions about what was wrong with him.

At first he was devastated to be sent from Atlanta to the New York Mets at the 2009 trade deadline—especially when he had to return to Atlanta six days later to play his old club. But as the Mets’ team plane took off after that series, the funniest thing happened: A sense of calm washed over him. He went 3-for-4 in the next game. “I was completely freed up after that,” he says. He still calls those two seasons in New York his favorite of a 12-year career that included that stellar start, the ’10 American League pennant with the Texas Rangers and a ’16 return to Atlanta before he retired.

When he speaks with young players now, he says, he tries to emphasize that in the end, a strong sense of self will carry you farther than a sweet swing or a filthy fastball. “You have to know you’re going to hit this adversity, and how you are going to deal with it,” he says. “And I think for a lot of these people, that’s the difference between them continuing to go up and becoming a superstar or just kind of flattening out.”

In some cases, he says, he has noticed that the hype starts in childhood. At his four kids’ youth sports games, he hears parents expecting the young athletes to do things they are simply not capable of at that age.

He coaches his seven-year-old daughter Ellie’s softball team, and for much of the season, he batted her seventh. “I’m like, ‘When she starts hitting better, I’ll move her up,’” he says. “That’s life, and that’s the expectation. And I think parents give these kids false expectations, or expect you to do something you can’t do.”

So he tries to tap the brakes on anointing young phenoms as the future, especially as a television analyst for Atlanta and on TBS.

“That’s the difference: Can you maintain it?” he says. “I think we see so many guys come up and they have flashes, and you think, Oh, my God, these are can’t-miss guys. But I think the key is: Can they make the adjustments? Can they keep up with the game? Can they do all these things they need to do to put themselves in that position? And unfortunately, us—because I’m, I guess, part of the media now—we put these expectations on these guys that, to me, sometimes they can’t reach.”

Instead he goes out of his way to discuss players such as Aaron Judge and Bryce Harper, who have proven they can star at the highest level. Francoeur knows how hard it is to get there, and he knows how hard it is to stay there. And he does reserve a soft spot for the ones who make a loud entrance. Can anyone be this good? Probably not—but it’s fun to watch them try.

This article was originally published on www.si.com as As He Finds His Stride in His Second Career, Jeff Francoeur Still Savors His Time as ‘The Natural’ .