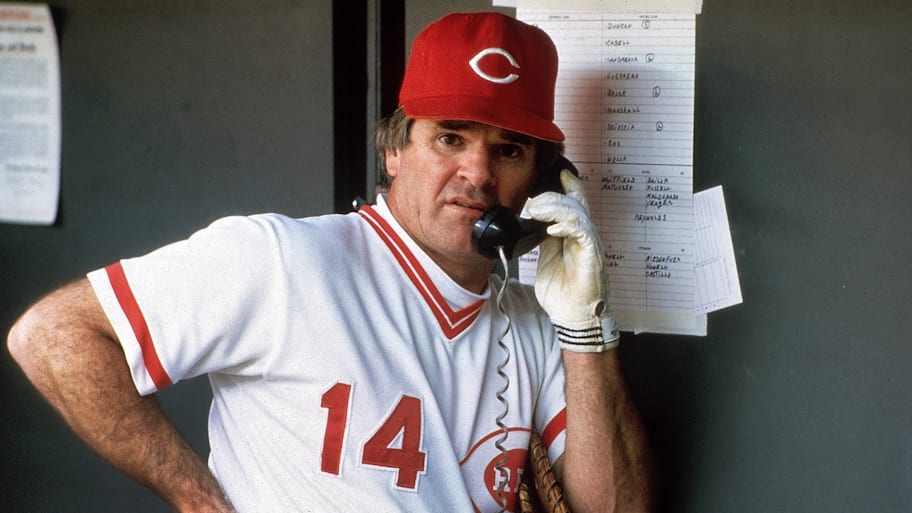

MLB commissioner Rob Manfred’s pace of play rules have been a nearly unqualified success, the World Baseball Classic has become must-see theater under his watch and he’s making real progress toward eliminating television blackouts. But when it comes down to it, he has one job. Nothing else matters if fans don’t believe what they’re seeing on the field is real. And with Tuesday’s decision to reinstate Pete Rose, the hit king who was banned from the sport for betting on baseball as manager of the Cincinnati Reds, Manfred has ensured that his legacy as commissioner will be one of failure.

Manfred announced Tuesday he had ruled that a person’s time on the permanently ineligible list ends at his or her death. That means that with Rose’s death in September at 83, he is now reinstated. (Manfred also reinstated 16 other people, including the members of the 1919 Chicago White Sox, who threw the World Series for money from gamblers.)

The decision makes Rose eligible for the Hall of Fame, which changed its rules after his ban to bar anyone on the permanently ineligible list from enshrinement. Manfred, predictably, insisted in a letter to Rose’s attorney that “it is not part of my authority or responsibility to express any view concerning Mr. Rose’s consideration by or possible election to the Hall of Fame,” passing that burden instead to the voters.

VERDUCCI: Pete Rose’s Competitiveness Drove His Rise in the Record Books—and His Downfall

Manfred has spent his decade as commissioner publicly talking about the integrity of the game and privately taking swipes at it. He failed to root out the pervasive use of technology to steal signs illegally in the mid-2010s, only taking action after Mike Fiers told The Athletic on the record in 2019 that the Houston Astros had used an illegal camera feed and banged on a trash can to alert hitters which pitches were coming during their ’17 championship season. Nearly everyone in the game had heard some version of this story by then—including the commissioner’s office, to whom the Oakland A’s, Fiers’s new team, had made similar allegations. Yet Manfred let it continue.

He reacted the same way to grumblings around the game that pitchers were using ever more outrageous foreign substances on baseballs to affect grip and spin rate, only taking action after publications including Sports Illustrated reported on the problem. Players and fans no longer trust even the composition of the sport's most fundamental piece of equipment after studies found discrepancies in the makeup of baseballs produced by Rawlings, which Major League Baseball owns. Star New York Mets first baseman Pete Alonso openly mused that the league might switch out baseballs depending on the makeup of future free agent classes to suppress salaries. So much of the discourse around baseball under Manfred's tenure has been about whether the sport is rigged.

But at least the Astros and the sticky-fingered pitchers were cheating the game in order to win games. Rose, who after decades of lying about it admitted in his 2004 memoir to having bet on baseball, has always said he only bet on the Reds to win. That might be true. But what about in the games in which he didn’t bet on the Reds? Are we sure he always turned to his best players in the moments of highest leverage? It is this competing incentive structure that makes Rule 21—don’t bet on baseball—the holiest of baseball edicts. If fans can’t be sure everyone involved is trying to win, the whole enterprise falls apart. This is the existential threat to the sport. It’s impossible to take it too seriously.

If anyone should know this, it’s Manfred, who in the past 14 months alone has presided over three public gambling scandals. On the eve of last season, Ippei Mizuhara, the longtime interpreter for Dodgers superstar Shohei Ohtani, admitted to having stolen millions from Ohtani to fund his illegal gambling habit. (Mizuhara is currently serving nearly five years in prison.) A few months later, Manfred put Pittsburgh Pirates infielder Tucupita Marcano on the permanently ineligible list for betting on Pirates games and doled out one-year bans to three other players for betting on baseball games not involving their teams. (The players agreed to their suspensions.) And this spring, Manfred fired umpire Pat Hoberg for sharing a legal sports-betting account with a friend who bet on baseball. (Hoberg has denied betting on baseball himself.) As sports betting becomes easier and more prevalent, this will only get more common.

Meanwhile, it’s hard to imagine a less savory character to whom to extend this grace. Rose agreed to the ban in the first place, then spent the rest of his life insisting he'd been wronged. He lied about betting on baseball until it became profitable to tell the truth. He even continued to bet on baseball! And when he wasn’t flouting the integrity of the sport or the integrity of the tax system, he was engaging in a deeply ill-advised—at a minimum—relationship with a teenager. In 2017, a woman identified as Jane Doe in court documents alleged that Rose had a sexual relationship with her for several years across multiple states in the 1970s, beginning when she was 14 or 15 and he was a married father of two in his mid-30s. Rose acknowledged the relationship but said they only had sex after she was 16, and only in Ohio, where the age of consent is 16. (The statute of limitations had long since expired, and Rose was never charged.) Asked about the episode by a female Philadelphia Inquirer journalist in 2022, Rose said, “It was 55 years ago, babe.” (The reporter said that Rose later offered to “sign 1,000 baseballs” for her.)

VERDUCCI: The Outsider: A Long, Strange Trip From Las Vegas to L.A. With Pete Rose

And the timing is also unflattering, coming as it does amid President Donald Trump’s campaign for Rose. The president tweeted in support of Rose in 2020, then again when he died in September. Trump doubled down in February, posting on social media that he would soon be “signing a complete PARDON of Pete Rose,” adding, “Baseball, which is dying all over the place, should get off its fat, lazy ass, and elect Pete Rose, even though far too late, into the Baseball Hall of Fame!” (Rose was never prosecuted for betting on baseball; any pardon would cover the tax-evasion charges to which he pled guilty in 1990 and for which he served five months in prison.) Manfred acknowledged last month that he had met with Trump and that the subject of Rose had come up.

Regardless of whom it benefits, the decision hurts the game. The Hall of Fame question will now fall to the Historical Overview Committee, a small group that meets next in December 2027 to consider players who made their greatest impact on the game before 1980. There’s a good chance Rose will get in. There’s a good chance Manfred will join him someday. After Tuesday, neither one will deserve it.

More MLB on Sports Illustrated

This article was originally published on www.si.com as Rob Manfred’s Pete Rose Flip-Flop Further Stains His Legacy.