Paul Skenes is numbingly consistent. With another gem Sunday against the Philadelphia Phillies (no earned runs in 7 2/3 innings), the Pittsburgh Pirates ace has allowed two earned runs or less in 32 of his 37 major league starts.

It may be easy to miss his brilliance over his first 13 months in the majors. Skenes’s excellence is obscured by Pittsburgh’s futility, its first three-game winning streak notwithstanding. The Pirates have been in last place in 106 of their 189 games since Skenes made his debut May 11, 2024. He has only four wins in 14 starts this year despite a 1.88 ERA because Pittsburgh is scoring fewer runs per game than any Pirates team in the past 108 years (3.15).

Attendance figures suggest even Pittsburgh fans may be growing accustomed to the greatness in their own backyard. Thus, we get ridiculous talk about trading Skenes because patience and perseverance, like nuance, is dying in a modern world that wants what’s next now.

The better solution than playing fantasy GM is to appreciate this historic figure in our midst. Wrap your head around this: Skenes may be the greatest pitching phenom of all time.

This much is unequivocal: nobody ever dominated at the start of their major league career with such a deep assortment of pitches like this. Skenes is the zenith of the Pitching Lab Era (or as I call this era of designer pitches, the three S’s: sequencing, shaping and spin). Now that he has added a wicked sinker, he throws seven pitches, six of them with a positive run value, while still blazing his four-seam fastball at 98.1 mph.

He has struck out batters with all seven pitches, including Kyle Schwarber with a UFO slider Sunday, only the sixth time all year he threw a two-strike slider to a lefty. Unfair.

A masterclass by Paul Skenes 😮💨 pic.twitter.com/ropI8BeVVg

— Pittsburgh Pirates (@Pirates) June 8, 2025

So, is Skenes really the greatest pitching phenom ever?

Let’s start with this measurement: the lowest ERA through 37 games in the Live Ball Era (since 1920), considering only those who started more than half of their 37 first games:

Lowest ERA Through 37 Games (Since 1920; Min. 18 GS)

Skenes is at the top, with the lowest ERA through 37 games in 105 years of pitching.

But “phenom” suggests something more than just efficiency. Stan Bahnsen, for instance, prospered in the late 1960s, the worst hitting era on record, and attracted little attention. Let’s face it, young strikeout pitchers grab our attention. So, let’s also look at the greatest strikeout phenoms through 37 games.

Most Strikeouts, First 37 Games

Phenoms everywhere. Skenes is 10th on this list, but in terms of strikeout rate he is second, behind only Stephen Strasburg. I’m inclined to require youth in defining “greatest phenom ever,” so let’s eliminate the three pitchers on the above list who reached 37 games in their age 26 season or later (Yu Darvish, Hideo Nomo and Matt Harvey).

Crosscheck the ERA and strikeout lists. Skenes, Jose Fernandez and Harvey are the only ones who show up on both lists. Fernandez and Harvey underwent Tommy John surgery after their 36th start, so Skenes has the edge there.

But let’s put down the calculator for a second. When it comes to phenoms, we must hold room for art, too, not just data. The best phenoms transcend the sport and become cultural icons. The three most iconic such phenoms were Mark Fidrych, Fernando Valenzuela and Dwight Gooden. I will add Strasburg to the group because he set the template for the modern phenom, when the hype builds before the pitcher even gets to the major leagues.

All of them show up on the top ERA list and/or the top strikeout list. So, if we combine stats and the “it” factor, we’re down to five phenoms. Which one was the best?

Top Phenoms, First 37 Games

There’s Skenes again at the top when it comes to WHIP and just behind Strasburg in strikeout-to-walk rate. (Alas, Strasburg was another phenom who blew out before reaching 37 games, needing Tommy John surgery after 12 starts.)

We need one more checkpoint: how much does a phenom carry his team? We can take a team’s record when the phenom starts (relief appearances not included) and compare it to how the team does when anybody else starts in that span during the time of the phenom’s first 37 appearances. The difference in win percentage between when the phenom starts and all others start is the Phenom Boost (PB):

Win Percentage With and Without Phenom

Fidrych aces this test. Fidrych made a bad Detroit Tigers team the equivalent of a 111-win team when he took the ball for manager Ralph Houk, who almost never took the ball away from him. As a 21-year-old rookie, Fidrych completed 24 of his 29 starts.

The Bird sold tickets, entertained fans, was the darling of the media, talked to the baseball, manicured the mound on his hands and knees and threw a bowling ball sinker while striking out very few batters. He was a joy who captured the spirit of “phenom” as much as anyone.

But Fidrych also blew out. He tore his rotator cuff in his 40th game (38th start) and was effectively done. Likewise, Strasburg’s PB is misleading because of so much time missed due to elbow surgery.

The 1976 Tigers were coming off two last-place finishes and ended up 24 games out with Fidrych setting the world on fire. In less reactionary times, nobody thought about trading a phenom like Fidrych.

In the same way, though much less quirky, Skenes is a rare asset you don’t trade on speculation that somebody’s top prospects are going to make you better five years down the line. The Pirates’ record for wins has held up for 101 years since Wilbur Cooper won the last of his 202 games. In the past half century only John Candelaria has won 100 games for the Pirates. The franchise is not exactly steeped in historic pitchers.

Skenes gives the Pirates an identity. He has a halo effect on the franchise, including his work ethic and drive to continue to improve that influence the team’s promising core of young pitchers. Greg Maddux pitched on six losing Cubs teams in seven years before leaving as a free agent. The franchise and all the pitchers who came through there were better for those seven years with Maddux. You trade young pitchers who are replaceable. You never trade young pitchers who look like all-time greats.

That said, Pirates owner Bob Nutting and GM Ben Cherington must be better at improving the team around Skenes. They failed massively in the winter at finding offensive talent. Eight years of drafts between 2016-2023 have produced a combined WAR of -1.01 from position players. The current roster has one homegrown hitter with an OPS+ greater than average: Andrew McCutchen, who was drafted two decades ago.

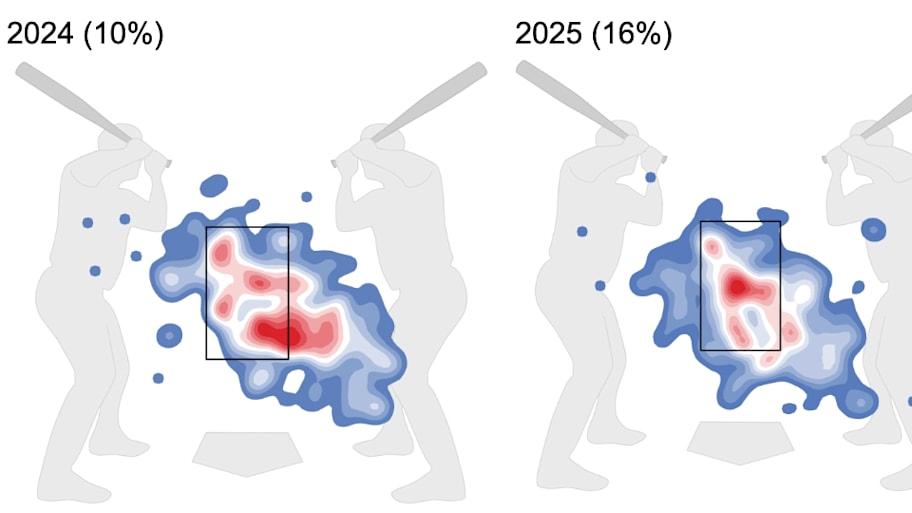

The lack of offense around Skenes is dulling the excitement of having him on the mound. Last season, when Pittsburgh had a winning record as late as Aug. 4, the Pirates saw a 24% boost in home attendance when Skenes started. This year the Skenes Effect is half of what it was last year:

Skenes Attendance Boost in Pittsburgh

The Pirates drew 29,026 fans for a Skenes Sunday start last June against the Rays. The one Sunday against the Phillies drew 3,765 fewer fans.

Meanwhile, Skenes keeps getting better. His phenom status is underappreciated because he looks so polished and stoic. Fidrych, Gooden and Valenzuela had a youthful joie de vivre that made them even more endearing. Skenes this year added the sinker to push righthanded hitters off the plate. Batters are hitting .125 against it.

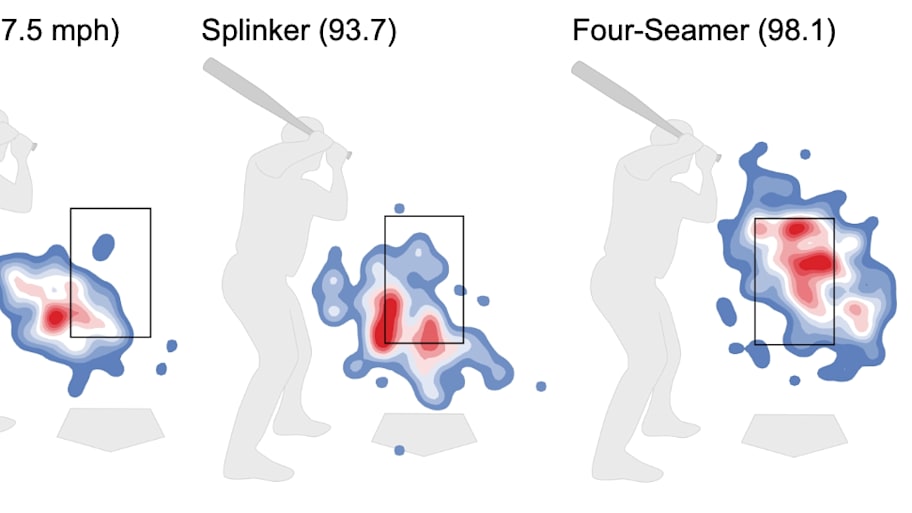

Imagine you are a righthanded hitter. Looking at his heat maps, you could get a 98-mph sinker that runs toward your hands, a 94-mph splinker (his turbo version of a splitter) that drops or a 98-mph four-seamer that rides high. Three fastballs, three speeds, three shapes.

Skenes Fastballs vs. Righthanded Batters

That’s before you even think about his nasty breaking pitches. The pitch Skenes is throwing more often this year is the sweeper, a pitch with a .111 batting average allowed in his career. Not only is he using it more, but he also is using it less as a chase pitch and more as an attack pitch that locks up hitters. Skenes gets more called strikes on his sweeper than any pitch but his four-seamer. As you can see from his heat maps, he is landing the pitch in the zone more, especially with some elevation.

Skenes’s Sweeper Use

Every time he takes the ball, Skenes gives a clinic on the evolution of modern pitching. The greatest phenom I ever saw was Gooden. He threw only two pitches, fastball and curveball, and dominated with both. He was so great he once told me if he had a lead he rooted for his Mets teammates to make outs so he could get back on the mound as soon as possible. It was that much fun. Keith Hernandez used to say the biggest game for the Mets was the day before Gooden pitched, because if they won it meant a guaranteed winning streak.

Now I see Skenes with an ERA half a run lower than Gooden (2.42) through 37 games and begin to wonder, is he better? Remember, though, that Gooden entered the height of his powers in his next 29 starts to finish 1985 (20-3 with a 1.52 ERA). Skenes has a long way to go to match Gooden’s first two seasons: 41-13, 2.00 ERA, 544 strikeouts, 66 starts, two strikeout titles and a Cy Young, all done at an age before Skenes was drafted.

Good luck topping that. The final call is yet to be determined, and it most likely will remain Gooden. But in the initial 37-game snapshot, and how well he executes a seven-pitch menu with precision and power, yes, Skenes is the greatest phenom to take the mound.

This article was originally published on www.si.com as Paul Skenes Is the Greatest Phenom to Take the Mound.