Welcome to the MMQB’s Quarter-Century Week. All week we’ll be publishing lists, rankings and columns looking back at the past 25 NFL seasons. You can find all those stories here.

Andy Reid is no different than most NFL coaches in that, when speaking to him, one must maximize their time. A coach’s day is rigorously scheduled, so much so that I was once given a copy of Tom Coughlin’s daily routine and saw that it forced him to take five-minute breaks for coffee and idle chit-chat. Reid, I’m guessing, is wired similarly.

One must have their questions prepared in staccato style and brace for the inevitability that an answer may clip off mid-sentence. Reid does not filibuster and instead conforms to the typical, pseudo-political patterns of speaking, avoiding extraneous fluff. He wants to get to where he needs to be on time.

However, what makes Reid different is that he almost always finds time and, in speaking to him, one picks up on a kind of paternal ease about him. I’m not a big energy guy, but some NFL head coaches are wound so tightly that interviewing them feels like standing next to a boiler about to explode. Reid is similarly rushed—like all head coaches—but has succeeded in never making anyone else feel that way.

I thought about this when I was asked to write about coaches at the quarter-century mark of the 2000s. Reid is an anomaly, mainly because of my hypothesis: Over the past 25 years, no job in professional sports has become more singularly complex than that of an NFL head coach. As such, no group of people in professional sports has become so incredibly wrung out and rattled. The rise in technology and analytics has raised more questions than it has provided answers. The increase in popularity of the NFL has brought more voices to the room and limited owners’ desire to be patient with a build, while also inviting a business-like approach that encourages owners to hunt for both wins and monetary savings simultaneously. The expansion of roster size and schedule length, along with the diminishing amount of time the NFL is not at the forefront of public consciousness, has limited the typical rest period, to the point where any break in a coach’s day, week, year, can hardly be considered a mental reset.

Yet, here is Reid, chuckling when asked a theoretical question about the future of quarterback play in the NFL, tapping you on the arm and saying how lucky he is that he hasn’t had to think about that in a while.

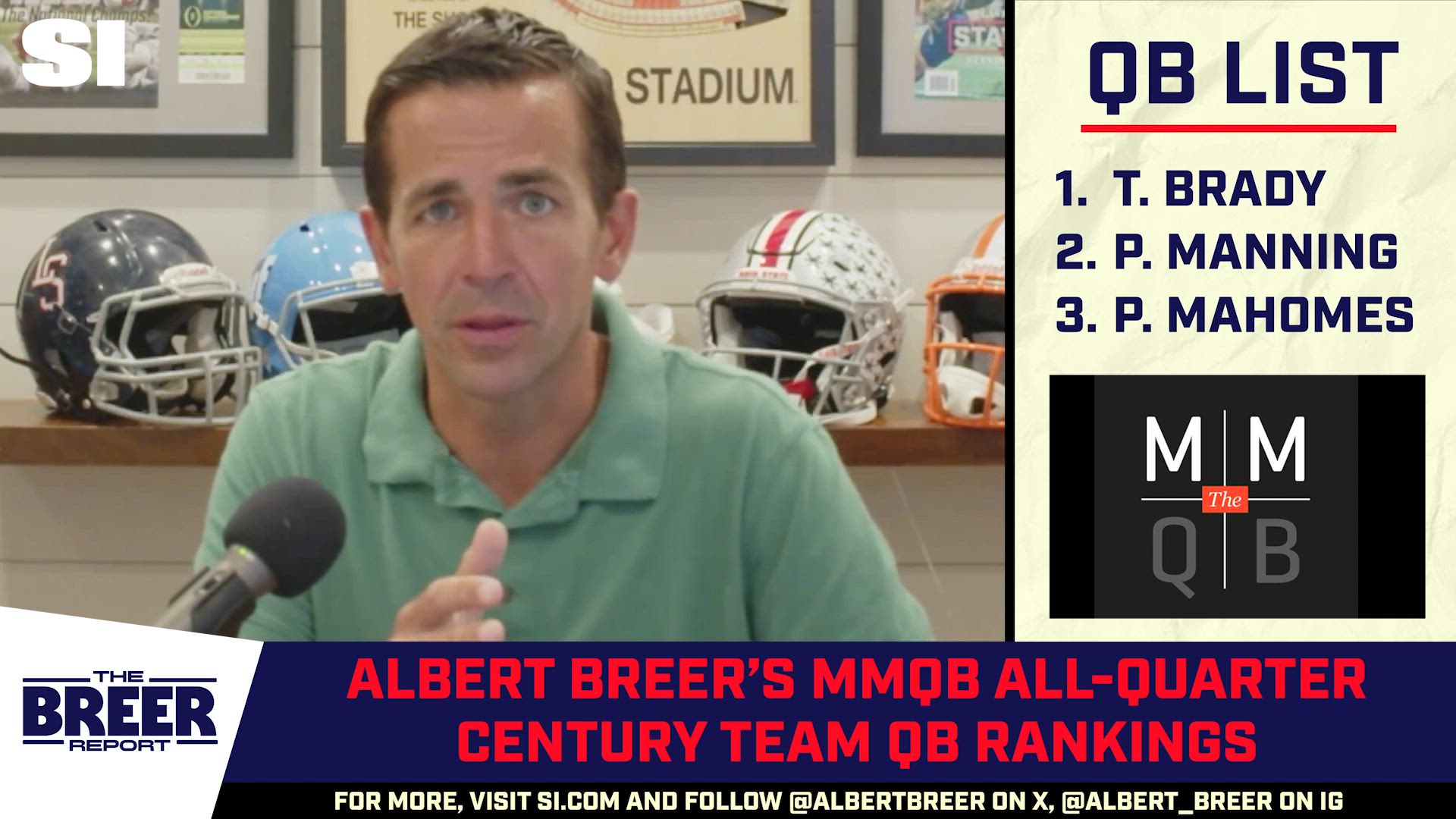

Reid, having Patrick Mahomes, stands at the heart of what I believe about the increased complexities of the profession. He was considered one of the truly good coaches in the NFL until he came into contact with one of the greatest clutch players in league history. Now he is on the fast track to becoming quite possibly the greatest head coach of all time. (Reid is 55 regular-season wins shy of Don Shula’s record, 347, and turned 67 in March. Should he coach until 74, which is the current age of the oldest head coach in NFL history, he would need to average about seven wins per season). Reid’s assistant coaches and coordinators, in part because of Mahomes, have the space and freedom to be among the most creative, researching and incorporating plays from ancient Rose Bowls or school playgrounds. This approach helps push away the drudgery and loneliness of an NFL season. This helps empower more individuals. This lifts an organization in unseen ways and forms the basis of the razor-thin edge that only the best NFL teams enjoy.

While technology has aided nearly every other professional sports enterprise, it has scattered the battlefield in professional football. More than 25 years ago, if a coach had an advantage, he could wield it like a cudgel for a season or more (think Mike Shanahan’s Broncos teams of the late 1990s). Now, because of the exactitude with which a team can break down and study an opponent thanks to advancements in film availability, sorting technology, automated grouping and processing speeds—never mind in-house analytical data that can cull a coordinator’s tendencies and offer insight into what plays they may call next—coaches are lucky if their game plans maintain relevance into the second quarter.

Armies of coaches are charged with scanning explosive plays, retrofitting them to their personnel (in itself a massively complicated job) and having them conform to a narrative structure, which is about the only way an offense can find a modicum of success now. Every play must also serve as a red herring, intended to set up deception later on in the game. Imagine graduating to the highest levels of professional coaching and needing to understand a plot twist on the level of Dostoevsky (that’s why you should never skip the reading list).

However, the ultimate hollowness of these efforts crystallized for me during an offseason chat with an up-and-coming offensive coach. We were discussing what kind of trends might emerge in 2025 after a ’24 season that brought exceptional, mind-blowing creativity to the forefront, alongside the popularization of the phrase “designer play-calling,” brought to the forefront thanks to Sean McVay, Kyle Shanahan and Ben Johnson. We are conceivably at peak access, peak brilliance, peak maximization and yet when I asked the coach what I should keep an eye out for when it comes to the evolution of football this season, he laughed and said, “Justin Jefferson” (the coach was not a member of the Vikings’ staff). Meaning: We can spend all this time trying to erase deficiencies and level the playing field, but there are a few alien monoliths in our midst, such as Jefferson, Mahomes, Lamar Jackson, Saquon Barkley and the like, who will completely ruin this noble pursuit for no explainable reason except their physical gifts and football instincts.

We can poke around at the other aspects of modern life that make NFL coaching so much more difficult—the digital age sapping the attention span of players, the NIL age babying them and teaching them to seek refuge when the atmosphere isn’t ideal, the modern CBA robbing players of valuable practice time, the rise in authoritarian-lite ownership and doofy tech-bro culture, which have forced coaches to adopt and incorporate horrendous cultural ideals that clash with their actual mission statements in real time—but most of them are incredibly familiar to anyone who has a job in any industry.

What seems unique in the NFL is that, despite all this, coaches are expected to do more, be more and produce more than ever before. The unsexy truth is that this is defined by some position coach sitting in a dark room watching six-second play snippets for hours on end, hoping to discover that 30% of the time an opponent tends to trip or get lost in coverage when the offense shifts into a trips formation from a two-by-two, and then prays that it actually happens during a game if that coach is lucky enough to get his concept absorbed into the game plan.

I think this stands in contrast with MLB and the NBA, for example, which were provided with more sensible and immediately applicable analytic blueprints that could quickly alter a team’s trajectory. To such an extent that, in the case of MLB, rules had to be instituted to counter the advantages created by data-based insights.

Of course, the humanness of all this is refreshing as we all confront AI doomerism. NFL coaching may be the last bastion against the supposed surge of computer-automated tasks. Computer assistance only makes their job harder and heightens the necessity for them to notice the fundamental elements of success and failure repeatedly, then attempt to stitch those concepts together into a cogent game plan. After all that, it requires the most human characteristics—faith and optimism—to pick up the pieces and try again.

While I did not cover the NFL 25 years ago, I believe there were more Andy Reid–like coaches. More people were relaxed enough to take the time to enjoy the ride—or at least make people around them feel like that was the case. This wasn’t necessarily because they had one of the monolith players who could peel them out of any sticky situation, but because the path toward improvement was far less complicated and the ability to remain that caliber felt far less threatening. Good teams with good processes, good plays and good players tended to stay good without fear of their advantage evaporating overnight.

Now, those—and only those—in possession of the one constant source of success (Mahomes) can stop and smell the roses.

More From MMQB Quarter-Century Week

This article was originally published on www.si.com as Being an NFL Head Coach Has Gotten Much Harder the Past 25 Years.