I lost track of how many times I got full-body chills while at Croke Park in Dublin in late July. The first time was when a taxi dropped me off at the stadium the day before the All-Ireland senior hurling final, and I saw the enormous stands towering above me. It happened again when I first set foot in the empty stadium as we filmed the latest installment of our Stadium Wonders video series. The chills returned repeatedly the following day, during the final between Cork and Tipperary—when the crowd roared as the two teams paraded around the field in the pregame ceremony, when the fans sang the national anthem in unison, when Cork scored the first point of the match 13 seconds in, and on and on.

As an Irish American whose interest in sports is primarily rooted in the traditions, history and communal aspects of fandom, it was a dream come true. I’d been dying to see a hurling match live ever since my first trip to Ireland as a 17-year-old. To have my first hurling experience be an All-Ireland final at the sport’s home was jaw-dropping. Most American sports fans probably aren’t familiar with Croke Park or the Gaelic games that are played there. Still, it doesn’t take an expert to appreciate the fast and physical game of hurling, or the iconic stadium that serves as the sport’s home.

Croke Park is, without exaggeration, one of the most culturally significant buildings in all of Ireland. The stadium is the home of the Gaelic Athletic Association, the governing body for Ireland’s indigenous sports of Gaelic football and hurling, but it’s also much more than that. Built nearly 150 years ago, the stadium is inextricably tied to Irish identity—in part because of its status as the GAA’s headquarters and in turn because of the GAA’s ties to the Irish independence movement. It’s a place where generations of Irish people have made some of their strongest sporting memories, where the island’s native games are played at the highest level, and where blood was spilled during the country’s fight for independence. And on Sunday, when the Vikings and Steelers kick off at 2:30 p.m. local time, it’ll play host to Ireland’s first regular-season NFL game.

To understand how important Croke Park is to Irish people requires a brief lesson on the country’s history and the conditions under which the GAA was founded. The late 19th century was a turbulent time in Ireland. The country was reeling from the loss of roughly one-third of its population due to the 1847 Great Famine and subsequent refugee crisis. Those who remained in the country endured efforts by British rule to squash Irish cultural traditions, most notably the native Irish language. In 1884, against the backdrop of this cultural crisis, a group of seven men met at a hotel in Thurles, County Tipperary, to form the GAA, to modernize and expand traditional Irish sports, as well as to preserve the native language and other elements of the culture. The first All-Ireland finals at the stadium that would become known as Croke Park were held 11 years later.

“In the 1880s, there was a real fear amongst Irish people that our pastimes and cultural exploits were receding at an alarming rate—and they were,” GAA director of communications Alan Milton says as he gave me a tour of the stadium. “The [GAA’s Gaelic] games have been front and center in Irish life ever since. There was a famous saying that the game spread like a prairie fire. Once one village set up a club, the next village wanted its club to be better than the original club. It was a domino effect.”

The fact that there are over 2,200 GAA clubs in Ireland today, and another 400 around the world, is a testament to the success of the founders’ mission, as is Croke Park’s status as one of the finest stadiums in all of Europe. Between 1993 and 2005, the stadium underwent a complete overhaul in which the aging stands were replaced one by one with a modern, state-of-the-art facility. (Demolishing and reconstructing one side of the stadium at a time dragged out the renovation process, but also guaranteed that Croke Park never missed an All-Ireland final during the construction process.) With 82,300 seats, it’s now the fourth-largest stadium in Europe and by far the largest in Ireland. Not bad for a stadium solely dedicated to sports that few outside Ireland have even heard of.

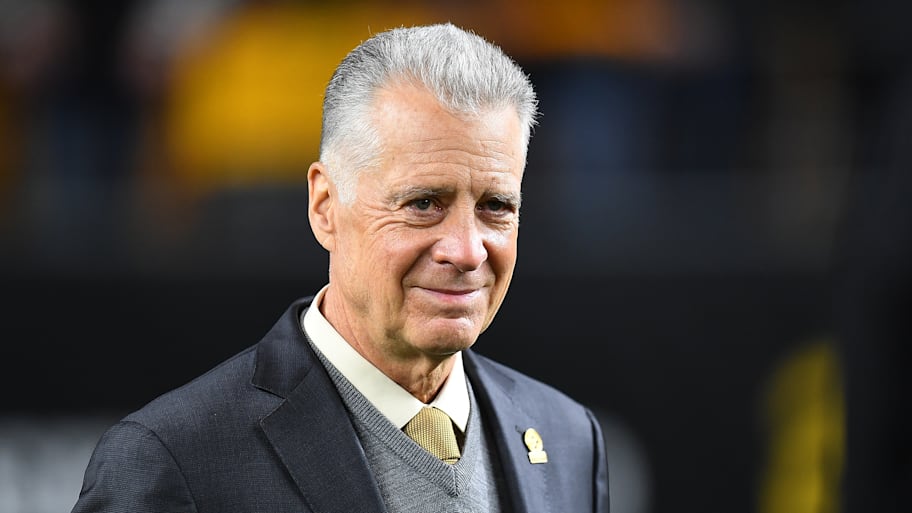

Some of the financing for these renovations came from none other than the owner of Sunday’s designated home team. “My dad started a fund with his partner, Tony O’Reilly, and many others back in 1976,” says Steelers president Art Rooney II, whose family emigrated from Ireland in the 1800s and bought the Steelers in ’33. “So they had funded a lot of different projects in Ireland over the years, and there was some money that went into Croke Park a few different times.”

From its inception, the GAA was closely associated with Irish nationalism. More than 300 of its members took part in the 1916 Easter Rising, a key moment in the Irish revolutionary period. In ’20, during the Irish War of Independence, the GAA was tragically thrust into the battle for a free Ireland when British soldiers opened fire on the crowd during a Gaelic football match at Croke Park between Dublin and Tipperary. Fourteen people, including Tipperary player Michael Hogan, were killed. As many as 100 more were injured.

The Gaelic games aren’t just sports. Rather, they’re a celebration and an assertion of a culture that has been under threat for centuries. And Croke Park is the spiritual and literal home of that movement.

“I suppose it’s a cathedral of Irish sport, but it’s more than just Irish sport,” Milton says. “It goes to the very essence of being Irish for a lot of people. It's in our DNA. [The stadium is] really sort of the nation’s playground in lots of ways. You know, lots of people have had some of their best days ever, either playing out there, if you’re one the privileged few, or in the stands supporting the people who are out there. It goes back to the very formation of the state and beyond. So it’s part of the emergence of modern Ireland in a very special way. And it really gets to the heart of our identity as a people, where you’re from, what part of the island you’re from, but also the diaspora.”

The two biggest days of the year at the stadium are the All-Ireland senior finals in hurling and Gaelic football. Still, Croke Park also hosts lower-profile matches, including junior championships and home games for Dublin’s inter-county teams. It’s also used as a concert venue. In between this year’s All-Ireland finals and Sunday’s NFL game, the stadium hosted two nights of Oasis’s sold-out reunion tour.

Like Croke Park, the GAA has also evolved over the decades. The organization has, understandably, long been wary of foreign influence. For decades, its official rules banned GAA members from playing or even watching “any imported game which is calculated to injuriously affect our National Pastimes.” Put more simply, members of GAA clubs weren’t allowed to play or watch rugby, soccer or cricket—sports viewed as reminders of Britain’s oppression. That rule was repealed in 1971, but an adjacent rule remained on the books that prohibited “British” sports from being played on GAA pitches. This became a source of controversy in the mid-2000s when the Lansdowne Road Stadium, the home of Ireland’s national soccer and rugby teams, was set to be demolished and replaced. The national teams needed another large stadium to call home during the redevelopment. After much consternation, the GAA agreed to allow the soccer and rugby teams to play home matches at Croke Park.

“It was a big deal when they allowed rugby and soccer to be played in Croke Park,” says Denis Walsh, a columnist for the Irish Times. “There was a lot of opposition to it among hardcore GAA people who saw soccer and rugby as being representations of Britishness, even though those games are very popular in Ireland. It took a lot of persuasion.”

The NFL’s trip to Croke Park is much less fraught because American football isn’t viewed as a threat to squeeze out Ireland’s indigenous games the way some see soccer and rugby. The financial benefit to the GAA from renting out the stadium to the NFL is also significant. The GAA is a volunteer-led organization. Its players are all amateurs, which means that more than 80% of its revenue is reinvested into its clubs all around the country.

“It’s a question of utilizing the stadium as best we can for the benefit of the organization as a whole,” Milton says. “Eighty-three percent of [the revenue that] comes in here goes back out [to the clubs].

“We don’t have extortionate player wages to pay. Obviously, we contribute to the players and their well-being through their organization called the Gaelic Players Association, but 83% goes back out. If you drive around Ireland any night of the week, you’ll see impressive facilities with floodlights, our clubhouses and pitches.”

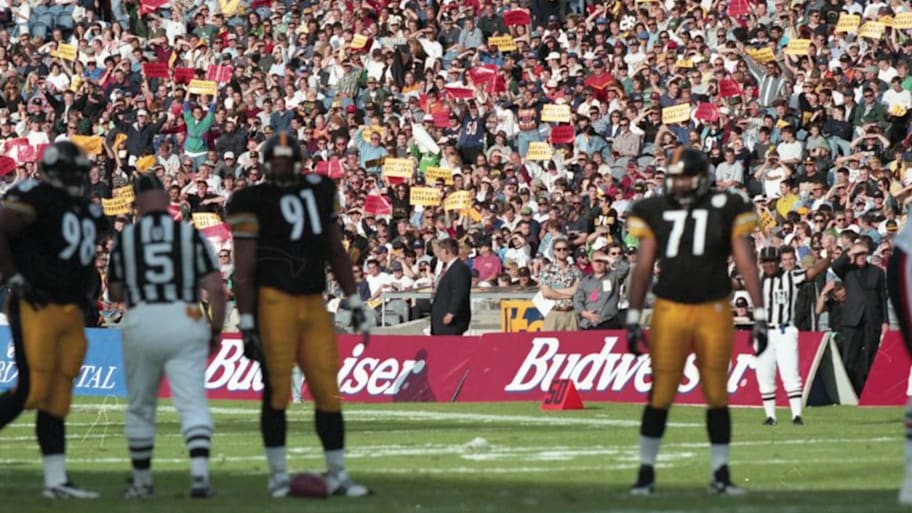

Croke Park has hosted American football previously on a couple of occasions. Two Britain-based U.S. Air Force teams played an exhibition there in 1953; Notre Dame beat Navy there in ’96; and Penn State beat UCF in 2014. This won’t be the Steelers’ first time playing at the stadium, either, having previously had a preseason game there in 1997.

“It was a fun trip,” Rooney says of that first game. “One of the fun parts about it was that the Bears were our opponent over there. The Rooney family and the Halas-McCaskey families go way back, and so we had a Waterford Crystal trophy that we gave to the winner, and my mother was very happy that we won the crystal trophy for that game. So it was a little different than your run-of-the-mill preseason game, let’s put it that way.”

Sunday’s game between Pittsburgh and Minnesota will be a continuation of the dual trends of American football’s increased presence in Dublin and the NFL’s ongoing quest for international eyeballs.

College football has become an annual fixture in Dublin, with Power 4 teams playing at Aviva Stadium, built on the site of the old Lansdowne Road Stadium, the home of Ireland’s national soccer and rugby teams. Two top-25 teams, Kansas State and Iowa State, opened their seasons there this year with a 24–21 Cyclones victory on Aug. 23. It was the fourth consecutive year that college football had been played at the Aviva. Two more games have already been announced for 2026 and 2027 (North Carolina vs. TCU, followed by Pittsburgh vs. Wisconsin).

The first regular-season NFL game played outside North America was in 2007, when the Giants and Dolphins played in London. The NFL has played at least one game in London every year since (except for 2020, because of COVID-19) and in ’22 began extending its reach to mainland Europe with a Buccaneers-Seahawks game in Munich. Two games in Frankfurt, Germany, followed in 2023, and the NFL returned to Munich last season. The Steelers-Vikings game in Dublin is one of seven games on foreign soil this year, the most international games in a single season. Along with the Chiefs-Chargers opener in São Paolo and three London games, the NFL will also be making its debut in Berlin (Colts-Falcons on Nov. 9) and Madrid (Dolphins-Commanders on Nov. 16). The league will head to Australia in 2026.

As a result, and as a result of the NFL’s increased presence on the other side of the Atlantic, Irish people are much more interested in and much more familiar with American football.

“I can tell you that the difference in just the awareness of the Steelers and American football in the country is just dramatically different than it was back in ’97,” Rooney says. “I mean, there are real fans there. They understand the game, they want to root for us, and so it’s just exciting to see how much progress has been made over there in the last couple of decades.”

The intense fan interest in Ireland led the NFL to prioritize Dublin as the host of a regular-season game as it continues to expand its international presence.

“I think one of the most apparent ways was the number of Irish fans that were coming to games in London,” says Henry Hodgson, the general manager of NFL UK. “So we were aware that there was a demand for the NFL in Ireland. Through the global markets program, we also had the catalyst of the Steelers wanting to choose Ireland as their global market to focus on. With that, I think that really created the momentum for us to collectively do more in the market. Very quickly, we saw how much fandom there was for the Steelers as well.

“That’s not to say that there aren’t other markets and other cities that we continue to look at now, but Ireland pushed its way quite quickly to the front of the line.”

The NFL has also seen a couple of Irish players enter the league in recent years. Jude McAtamney and Charlie Smyth are kickers on the practice squads of the Giants and Saints, respectively, and both played high-level Gaelic football before making the switch to the gridiron.

“It feels like in the same way that maybe Australia 10, 15, 20 years ago, the pipeline of punters was finding their way into the NFL, it feels like there’s an emerging pathway for Irish kickers—a lot of them from from GAA—who could find their way into into the NFL as well,” Hodgson says. “I think that’s another kind of exciting piece, and was certainly a contributor to Ireland’s interest in the NFL, which has then led to a game in Ireland, has just been how proud they are of the Irish players that have [signed with NFL teams].”

The NFL is highly intentional with its approach to international expansion, though. It isn’t just about hosting one-off games in far-flung cities. The league wants to make sure that wherever it goes, it’s building a sustainable fan base. Hodgson doesn’t want the NFL’s international games to be “cookie cutter” or have the league feel “we’re like the traveling circus.”

“I think it’s being done in a way where we’re looking at how do you develop an NFL fan base in a market,” Hodgson says. “And then what part does playing a game there play in developing that fan base—and sort of when’s the right moment to do that? Is it as a catalyst to springboard more fandom or is it a reward for the fans that already exist?”

The NFL also wants to strike a balance between bringing its own distinctly American brand of entertainment to the world and respecting the local culture in the cities it visits.

“I think a mini Super Bowl is a great descriptor for this,” Hodgson says. “That comes with the cultural pieces that you would find with the Super Bowl. For the most part, especially when you’re going into new cities, what people know the NFL for is a great sporting spectacle but also then the entertainment piece. We want to make sure that we have exciting, locally relevant, culturally relevant halftime shows and other entertainment pieces built into the games.”

This season’s record number of international NFL games is just the tip of the iceberg, though. Commissioner Roger Goodell said last year that he hopes to have as many as 16 annual games abroad, an increase that would come in conjunction with adding an 18th regular-season game. (The longer schedule would “open up more inventory to allow us to play more globally,” he said in November.) Speculation about a potential Super Bowl in London has been percolating for years, and Goodell confirmed in 2023 that it was something the league had explored.

Rooney says a strong international presence is “very important” to the league’s future.

“I think the league wants to have a large international presence and compare our league to the other sports leagues that have international followings,” he says. “So I think it’s something that’s important to the future of the league if we want to grow to compete with and really be in the same sort of category as some of the soccer leagues and Formula One and things like that.”

There’s something ironic about the ultimate American sports league’s quest for world domination, including a stop at this quintessentially Irish stadium. The other stadiums that have hosted or will host overseas NFL games are undoubtedly iconic. They include Wembley Stadium in London, the Bernabéu in Madrid and Munich’s Allianz Arena—some of the most famous soccer stadiums in the world. But none of them are tied to their home country’s national identity in the same way that Croke Park is.

The Steelers-Vikings game in Dublin is primarily an opportunity for the NFL to expand its global footprint, but it should also be an opportunity for American fans to familiarize themselves with one of the most iconic sporting venues in the world—and a stadium and a sport that are unlike anything we have in the United States.

The All-Ireland senior hurling final in late July between Cork and Tipperary was the most remarkable sporting event I’ve ever attended. I spent much of the previous day talking to Irish people who’d come from all over the country for the match about what Croke Park and the GAA means to them. From the moment I stepped outside my hotel on game day, the significance was evident. Every pub I passed on the two-mile cab ride to the stadium was jammed with people in Cork and Tipperary jerseys. Street vendors sold cords of thread in each team’s colors for supporters to drape around their shoulders, tie around their wrists or knot in their hair—and almost everyone bought one. I could imagine these same streets and pubs soon filled with fans wearing NFL jerseys.

Milton had told me to expect a late-arriving crowd, explaining that most fans would linger in the pubs until close to game time before making their way to the stadium. So when I turned the corner onto Jones’ Road roughly 20 minutes before the stadium gates were set to open and more than two hours before the start of the match, I was shocked by the sea of people assembled in the street. This was the first time that local rivals Cork and Tipperary, the two most successful counties in the history of the All-Ireland hurling championship, had met in a final, and the fans were raring to go.

On a personal level, the fact that it was Cork vs. Tipperary was unbelievable. All eight of my great-grandparents were born in Ireland. One great-grandfather on my father’s side (Denis Walsh, not to be confused with the journalist quoted above) was from Cork. On my mother’s side, one great-grandmother (Mary Brennan) was from Cork, and the other (Nora O’Dwyer) was from Tipperary. What are the odds that those would be the two teams playing in a match I’d spent so long dreaming of seeing? The night before the game, I’d leaned into the family aspect of the experience by going to a pub called The Duke, where my fourth-great-grandfather, William Gartland, had been living when he died in 1882.

Inside the stadium, the atmosphere was enough to give me goosebumps. The highlight of the pregame ceremony was when the two teams paraded around the perimeter of the field—a bit of pomp and circumstance unique to the Gaelic games that allows the tension to build inside the stadium as the rival fans try to cheer loudest when their team passes in front of their section. The fans then channeled all that energy into singing the national anthem. In the U.S., the frequency with which the anthem is performed can make it feel perfunctory. At Croke Park on All-Ireland final day, though, the anthem is an incredibly moving experience. There is no celebrity at midfield with a microphone—only an instrumental track piped in over the sound system as 82,300 Irish people sing the anthem in the language the British spent centuries trying to eradicate. It was in that moment that I understood what Milton meant when he said that All-Ireland Sunday at Croke Park is “the day when lots of people feel the most Irish—even more so than St. Patrick’s Day.”

Hours after the final, I was in a pub in the center of town and struck up a conversation with a man named Neil McManus, a former inter-county hurler for Antrim who had been part of the BBC broadcast of the match. When I told McManus who I was and what had brought me to Dublin, his eyes lit up and he called across the room to a man named Shane.

“Shane, you have to meet Dan,” he said.

Shane looked like most of the other men in the bar—average build, early 30s, holding a beer. But Shane, McManus told me, was Shane O’Donnell, the reigning Hurler of the Year. Translated into American terms, he was the MVP of the league. His team, County Clare, had won the 2024 All-Ireland but had fallen short this year. And here he was, in a bar after the championship game, hanging out with a bunch of regular folks and not getting constantly mobbed for selfies. It’s like if Josh Allen had blended in with the crowd at a bar on Bourbon Street after last season’s Super Bowl. That’s what makes the Gaelic games special. They simultaneously feel larger-than-life and intensely local.

Thousands of American NFL fans will make the trip to Dublin this weekend to see their team play and will undoubtedly make lifelong memories there. The NFL is hoping to tap into what makes the experience of being in Dublin on an All-Ireland Sunday so special, as the league looks to export its game to every corner of the globe. Just don’t expect to run into Aaron Rodgers or Justin Jefferson in a pub after the final whistle.

This article was originally published on www.si.com as There’s No Better International Venue for the Steelers Than Croke Park .